Community Preference in NYC

There’s an interesting conversation beginning to pick up steam in New York this week. It has to do with a bit of trivia around a program called Community Preference, which sets aside 50% of affordable units in new developments for current residents of the neighborhood (defined by community boards – the city is comprised of 59 of them).

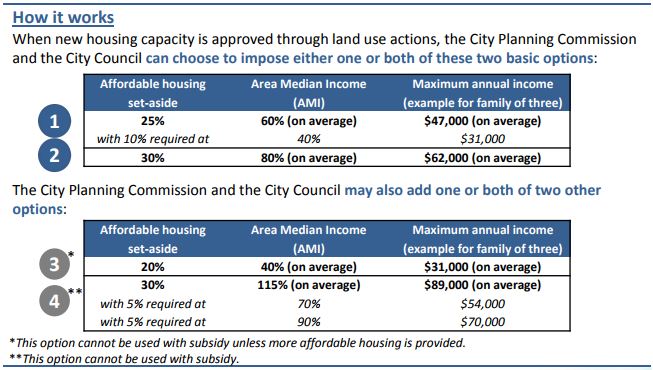

The questions surrounding the efficacy of the Community Preference program is taking on new urgency under Mayor Bill de Blasio’s new programs for housing affordability. Last year, de Blasio passed the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program. The following table (originally here) gives a high-level overview of the program:

Broadly speaking, MIH requires that developers either provide a few units at a very low price, or more units at a slightly higher rate. Developers are generally free to choose which of the options they’ll employ. Last week I wrote about how Area Median Income is often used as the basis for determining whether or not housing is affordable. In NYC, AMI for a family of 3 is $85,900. As AMI goes up or down, developers are required to adjust the rents charged for these units.

MIH certainly has its merits, and it is doing a good job of committing developers to providing affordable housing for New Yorkers. There’s currently a lot of building happening (though, and I feel like I say this every week, not enough) and MIH allows the city to piggyback, to an extent, off the private market’s desire to buildbuildbuild. (As an aside: lots of people think that the creation of new units is the most important part of an affordability strategy, and that most of what de Blasio is doing on the affordability front is tied to MIH. Those are both incorrect, as this real smart piece from City and State this week lays out)

Because MIH explicitly relies on setting aside affordable units in market-driven developments (as have other affordability projects), there’s a renewed interest in how the community preference system works. The Pacific Park project being built near Barclay’s Center (pictured at the top of the post), for instance, includes 298 below-market apartments (though it is not being built under the MIH program). Of these 298, 50% (149 units) are slotted for folks who already live in the neighborhood. The other 149 affordable units are open to residents anywhere in the city.

So what’s wrong with setting aside units for people already in the neighborhood? On its face, it seems like a completely reasonable program. Longstanding members of the neighborhood get first dibs on units, which can preserve the community. This can be especially important in gentrifying neighborhoods, where there are very real concerns about displacement. What’s more, the program is good politics; the prevalence of NIMBYs and the power of NYC’s community boards mean that neighborhoods can extort a high price for new development in their neighborhood.

There are two big reasons why the community preference program actually undermines the city’s efforts to integrate residents of different economic backgrounds, both of which are little bit wonky.

The first revolves around the fact that the Area Median Income numbers are set at the metropolitan level. While AMI makes sense in some parts of the country, in a metro region of more than 20 million people, its use breaks down quickly. While the AMI for a family of 3 is $86K as stated above, that number masks enormous variation at the local level. In East New York, the first neighborhood to be rezoned under MIH, the median household income is less than $35,000 – less than 40% of AMI. If you refer back up to that table from the City, you’ll see that affordability levels are often set to either 60% or 80% of AMI. What the City calls “affordable”, then, is actually more than the median family in East New York is able to pay. Market rate housing is already, by and large, “affordable” in East New York and other similar neighborhoods, meaning that MIH has little impact. In Greenwich Village, on the other hand, median family income is $150,000, nearly double AMI. Here, affordable units are significantly cheaper than the market rate units.

Being the recipient of community preference in Greenwich Village, therefore, is significantly more valuable than having community preference in East New York. Because of how AMI and affordable housing incentive schemes are structured, community preference results in a much higher benefit for residences already living in high-income neighborhoods. Unsurprisingly, these high-income neighborhoods enjoy better public services, better schools, and better access to jobs. Community preference, therefore, disproportionately benefits city residents who are already receiving big benefits from their location in these neighborhoods.

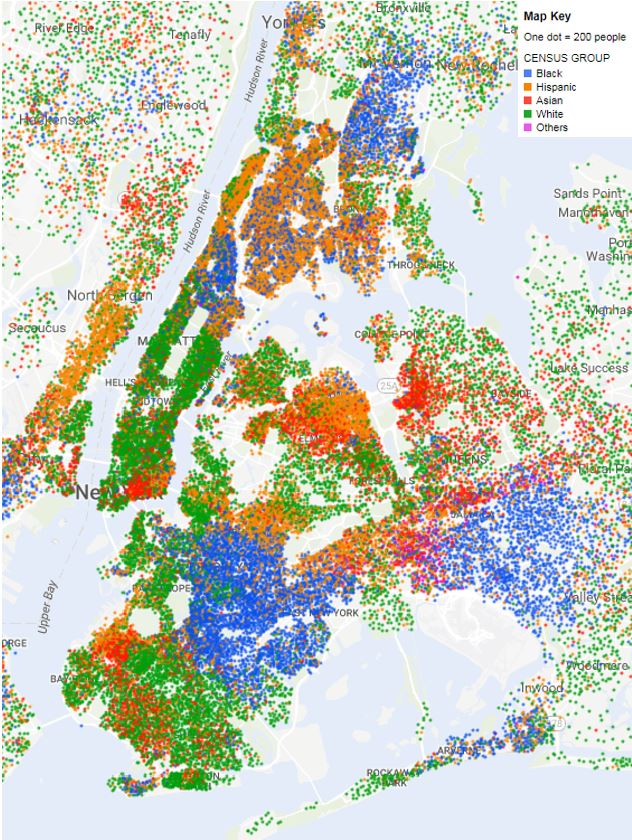

The second major problem with the community preference system stems from the city’s persistent residential segregation patterns:

If you’ve been to this blog before, this is going to be old news, but an enormous amount of these patterns can be traced back to redlining, restrictive covenants, and other tactics that have been used to enforce residential segregation since the 1940s. This week I wrapped up American Apartheid, a book chronicling the history and persistence of housing segregation in the United States. Though it was written in 1993, little has changed in the last quarter century (the map above, an op-ed in the NYT last week, and census data make this abundantly clear). As Erroll Lewis laid out in the Daily News last week:

Black New Yorkers make up about 23% of the city’s overall population, but are less than 5% of the population in 17 of the city’s 59 community boards. Latinos are 29% of the city, but make up less than 10% of the total in 10 community boards.

Because only 50% of affordable units in predominantly white community boards are made available to residents elsewhere in the city, the community preference program supports the continuation of the status quo segregation in the city.

It’s no wonder why community preference came into being in the city. The politics of it are too easy to resist. But when a system claiming to be working on behalf of community justice actually benefits those already receiving benefits and reinforces the city’s residential segregation, it’s time for it to go. To that end, a group of 3 New Yorkers are suing the city precisely because of the discriminatory impact of community preference. Let’s all cheer them on.